Just food explores how the Finnish food system should change in order to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions significantly. A particular area of interest is the fairness of changes. For this reason, the project looks into the economic impacts of the emissions reductions on different agricultural production sectors and nutrition impacts on different population groups. In addition, it assesses how the emissions reductions of the food system influence other environmental goals, such as the reduction of eutrophication and the protection of biodiversity.

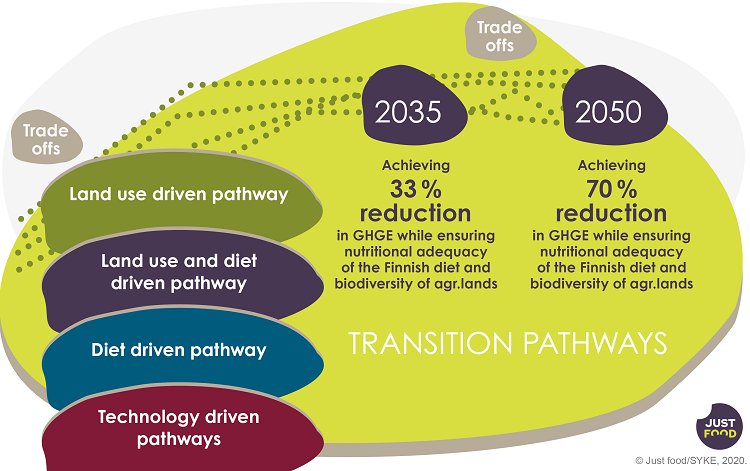

To determine the impacts, Just food has developed five different transition pathways, or sets of measures targeted at different stages of the food system, with which the emissions reductions could be achieved.

A low-carbon food system may be pursued with changes to consumption habits, agricultural land use changes or new technology and innovations in agriculture and food industry.

Transition pathways as the methodological glue

As the impact of emissions reductions are looked into from many different perspectives, research methods also have to be considered carefully.

“Fairness is the thematic glue in our project and the transition pathways act as the methodological glue. They help outline potential difficulties and problem areas in the transition to a low-carbon food system”, explains Jyrki Niemi, Research Professor at Luke.

The transition pathways differ from each other so their different impacts can also be made visible.

In addition to the land use driven, diet driven, agricultural technology driven and food innovation pathways, a combined land use and diet driven pathway is used.

The pathways’ set of measures includes, for instance, decreasing the cultivated peatland field area and replacing meat and dairy products with other products. New technologies, energy consumption and innovations in agriculture and food industry are also areas of their own.

With the aid of the transition pathways, the impacts of emissions reductions can be determined. © Just food/SYKE

Modelling is based on “What will happen if...” thinking

In reality, emissions decrease as a result of a combination of different pathways and measures. Outlining an extensive, complex entity and analysing the joint impacts of different measures is difficult with qualitative methods only. With the aid of models, the impacts of the transition pathways can be scrutinised more systematically, starting from the idea “What will happen if...”. This also makes it possible to determine the distribution and fairness of impacts.

In the transition pathways, the starting point is looking after people’s nutrition and biodiversity, but modelling makes it possible to dig deeper. For instance, are there population groups whose nutrition would be impaired by some measures? Do the measures’ economic impacts on agriculture vary in different parts of Finland? How do emissions reduction measures improve or deteriorate biodiversity?

This ensures that we do not recommend policy measures that would impair the nutrition of already vulnerable groups, for instance.

Or if significant restrictions were imposed on the use of peatland fields, should income losses be compensated with policy measures? This, too, is one of the key questions in a just food transition.

Difficult questions are discussed together

The emissions reduction target of the transition pathways is set at 70 per cent by 2050. The milestone by 2035 is a 33 per cent emissions reduction.

When the targets are clear, the measures needed for achieving them can be outlined by going backwards along the timeline. This is called the backcasting method. It requires an understanding of how the situation would develop if no changes were made. This is called the baseline. A practical example of a baseline is the development of greenhouse gas emissions in the food system by 2035 if no new emissions reduction measures are taken.

This comparison has been analysed during the first year of the project while building modelling tools at the same time.

The researchers from Luke, the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) and the Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) have had many important questions to answer. What kinds of diets will be used in addressing emissions reductions and what products will replace meat and dairy products, for instance? What happens to farmland that is no longer used for agriculture? What kinds of political instruments are in use and what is the role played by imported food? Even difficult questions need to be answered to ensure that the models set off on the right track.

“Our current selection of food products is enormous and constantly changing. A good, nutritious and sustainable diet can be built in many ways. Even though the basic guidelines of a nutritious diet and a sustainable diet are similar, there are also challenging choices, such as reducing dairy products in the diet. It is not only a question of a consumer’s choices but of far-reaching impacts”, notes Liisa Valsta, Research Manager at THL.

Modelling needs many kinds of data

A key starting point for modelling work is detailed and up-to-date information about food consumption from different socioeconomic groups within the adult population. This was collected in 2017 in connection with THL’s national FinDiet survey. Other sources used are the versatile nutrient content details of the national food composition database Fineli, databases describing the food selection in retail stores and Luke’s and SYKE’s constantly developing information on the differences between the environmental burden of food produced in Finland and imported food.

However, there is no nationally representative food consumption information regarding children and young people in Finland.

Information about food consumption by certain vulnerable groups is also limited. As a result, with regard to these groups, modelling has to make assumptions on the basis of limited data that is even more than 10 years old.

Modelling is an extremely extensive activity with plenty of different aspects to take into account. For instance, environmental impact assessment is not only about climate.

One of the challenges is related to the development of diversity indicators. For this reason, in summer 2020, a research project on insect and plant diversity was carried out on Southern Finnish fields where grain, fodder plants and field vegetables were grown.

Comparison of methods increases reliability

Modelling uses information produced by different models. Luke’s Dremfia sector model studies the impacts of the alternative transition pathways on agricultural production volume, its geographical location and farmers’ income. The food system model developed by SYKE in the Just food project describes the environmental and economic impacts of food production and consumption in the entire Finland’s national economy, including imports and exports. The model produces comparable environmental impact information about a wide range of food products.

Luke’s FoodMinimum model is based on the life cycle analysis of products and combines their environmental impacts and nutrition. The model makes it possible to compare the environmental impacts of different diets. The aim is to produce environmental impact coefficients, which would be combined with THL’s Fineli database.

This would make information about the environmental impacts of food products widely available to the general public and food service operators.

“The comparison of different methods makes it possible to compare the environmental impact coefficients that have been produced in different ways. This enables us to assess and improve the reliability of information significantly”, says Jani Salminen, Head of Unit at SYKE.

Putting information into use

The first modelling results are expected during 2021. At that point, there will be information available about the kinds of direct and multiplier effects different emissions reduction measures could have. However, modelling is demanding and complex scientific activity and some things are very difficult to model.

“Understanding the diverse interdependencies of nutrition, food production, climate and the environment and modelling the related feedback relations will inevitably make the model extremely complex. However, at its best, modelling increases our understanding of the relations and dependencies of challenging entities,” Jyrki Niemi, Research Professor at Luke, points out.

Finally, this information will be turned into a suitable format for decision-makers’ use, in order to ensure that when pursuing emissions reductions, the impacts of these reductions can be assessed and, if necessary, balanced.

Along with the food transition, more information is needed in nutrition policy decision-making, for instance.

“Replacing products of animal origin with plant-based products partly requires nutrient supplementation so that the population’s sufficient nutrient intake can be guaranteed. This has already happened with plant-based beverages that replace milk, for instance. As the selection of plant-based food products expands, the principles of dietary supplementation recommendations and practices must be discussed as part of nutrition policy decision-making,” estimates Liisa Valsta, Research Manager at THL.

More information

- Research Professor Jyrki Niemi, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), firstname.lastname@luke.fi

- Research Manager Liisa Valsta, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), firstname.lastname@thl.fi

- Head of Unit Jani Salminen, Finnish Environment Institute SYKE, firstname.lastname@syke.fi